Railroading in Cajon Pass

Steam engines, Cajon Pass - Photographer Unknown (colorized)

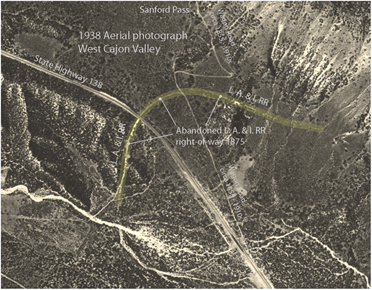

The first attempt to build a railroad line through Cajon Pass was in 1875, when the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad Company sought to connect the silver mines in central California's Owens Valley to Santa Monica on the Pacific Coast. A 20-mile length of track was completed between Santa Monica and Los Angeles, with plans to extend the line to San Bernardino and lay track up the west side of Cajon Canyon and through the pass. Plans for the route included a 3,700'-long tunnel to carry the line under the ridge at the upper end of the canyon and onto the desert floor. Grading work and tunnel excavation commenced in 1875; however, an end to the mining boom brought construction to a halt soon after it began (Duke 1995:69-70; Hockaday and Hockaday 2007:174; Walker 1978:1, 3).

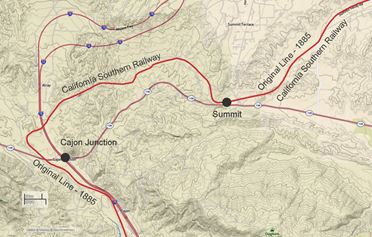

In September 1883, the California Southern Railroad completed its line from the Port of San Diego to San Bernardino and prepared to extend the line 81 miles north through Cajon Pass, where it would join with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad at Waterman (present-day Barstow), California. In 1884, the California Southern Railroad, which had been acquired that year by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) (then "Railroad"-the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad became the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway in December 1895), began constructing the line from Waterman southwest to the Cajon Pass summit. South of Victor (later named Victorville), the line began a long ascent from the Mojave Desert to the high mountain divide that separates the desert from the coastal region. Construction of the line from San Bernardino to Cajon Summit began in January 1885. Teams of seasoned Mexican graders began clearing a right-of-way (ROW) at the lower end of Cajon Canyon, and, by July, the workers had graded approximately 19 miles of roadbed. Joined by a large contingent of Chinese laborers, the grading crews launched an assault to clear the ROW up the steepest and most rugged part of the canyon. The grading crews created a serpentine alignment through deep cuts as the roadbed wended up the canyon to the summit. Rather than dig two or more tunnels, the laborers carved out the mountainside and used the dirt from the huge cuts to fill low spots along the alignment. Tracklayers followed the grading crews and laid 61-pound rails through Cajon Pass using ties that were obtained from lumber mills in the San Bernardino Mountains. On November 9, 1885, construction crews joined the two sections of railroad just below Cajon Summit. Two days later, a train carried railroad officials and local dignitaries from San Bernardino to Waterman (Barstow) (Bryant 1974:96-101; Duke 1995:58-59, 70-72; Robinson 1990:34).

The original, single-track line through Cajon Pass headed north from San Bernardino for about 2 miles before turning northwest and continuing on a steady 2.2-percent grade. After crossing to the west side of Cajon Creek, the track entered the lower end of Cajon Canyon and followed the west side of the canyon for several miles. The line passed through Blue Cut, then crossed Cajon Creek and followed the channel's east bank to Cajon Station. Leaving Cajon, the track crossed to the west side of Cajon Creek and continued up the canyon for more thanl mile, then headed northeast, crossing to the creek's east side. At this point, the rail line passed through deep cuts and over fills through rugged terrain as it climbed to Cajon Summit, 3,822' ASL. The track between Cajon and the summit climbed the pass at a 3.4 percent grade. Keenbrook, Cajon, and Summit were major stations along the rail line and were equipped with train order offices, section gang facilities, signal maintenance personnel, and, at Keenbrook and Cajon, water for the steam engines (Walker 1978:8; 1985:68, 71, 73, 79, 81).

In the ensuing years, freight and passenger trains increased in size and weight. Even with helper engines, the longer, heavier trains moved slowly up the 3.4-percent grade, causing traffic in both directions to bunch up. To complicate matters, in 1905, AT &SF and the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad, entered into a trackage-rights agreement that allowed the latter company's trains to operate over Cajon Pass. With this increase in rail traffic, the single-track line through Cajon Pass, even with passing sidings, had become a bottleneck (Bryant 1974:191; Duke 1995:72; Walker 1978:8).

Sullivan's Curve

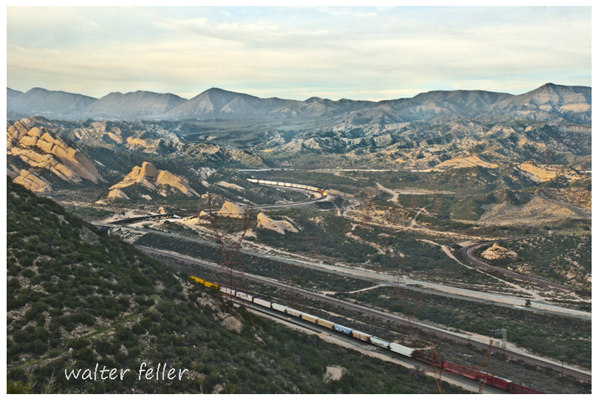

The steep grade between stations at Cajon and Summit created problems for train operations over the pass. In the early 1900s, AT &SF initiated plans and surveys for double-tracking the line from San Bernardino to Cajon Summit on a constant grade of 2.2 percent. Construction out of San Bernardino commenced in 1910, and, by 1912, the new track, which was laid on the existing 2.2-percent grade, extended to Cajon Station. Traveling north from San Bernardino, the two tracks paralleled one another until reaching Cajon Station. To maintain a constant 2.2-percent grade from Cajon to Summit, AT &SF engineers proposed a route that would take the second track west and north of the original line. This meant that eastbound trains ascending the more favorable grade would operate to the left of the original line, a rarely encountered feature in the United States. At the upper end of the Cajon siding, the new track diverged to the west of the original line on a 10° curve and crossed to the west side of Cajon Creek. From there, the track headed west for approximately 1/2 mile, then made a sharp 10° turn to the north and continued in a generally north-northeast direction.

The giant curve above Cajon Station was named Sullivan's Curve after Herb Sullivan, a citrus farmer from Placentia, California, who, during the 1930s and 1940s, photographed trains as they rounded the curve. After emerging from Sullivan's Curve, the new line roughly paralleled the original line for about 1 mile (at a slightly higher elevation), headed northwest, crossed to the east side of Cajon Creek, then gained elevation before turning east. The two tracks rejoined their parallel alignment near Cajon Summit. About 3 miles below the summit, construction crews blasted two tunnels. Both tunnels were constructed with timber supports, but were soon lined with concrete after passing locomotives repeatedly set the fire to the timbers. By December 1913, the line was double-tracked all the way to Cajon Summit. This circuitous route made the new line 1.9 miles longer than the original line but provided a constant 2.2-percent grade for trains moving uphill to the summit.

Bridges were constructed to carry the second track over roadways and drainages. New sidings were installed at Keenbrook, Cajon, and Summit Stations to provide each main track with side tracks for meeting or passing trains. Sidings were placed at the minor stations of Alray (named after AT&SF employee Al Ray) and Pine Lodge. A 2,200'- crossover near Pine Lodge Station (located on the eastbound track between Cajon and Alray Stations) allowed movements from the eastbound to the westbound line, or vice versa. The crossover was removed in 1948. Double-tracking the 55 miles of rail line from Cajon Summit to Barstow commenced in November 1923 and was completed in March 1924. For organizational purposes, AT&SF referred to the 81-mile line between Barstow and San Bernardino as the First District of the Los Angeles Division, with mileposts numbered westward beginning with 0 at Barstow (Duke 1995:72-75, 79; Walker 1978:15, 17, 22, 77-78).

Heavy rains in February and March 1938 resulted in major flooding along Cajon Creek and its tributaries. The floods washed out tracks and bridges, halting all rail traffic through the pass. Following the flooding episode, AT&SF rebuilt bridges (using construction techniques to prevent scouring around and under the piers), constructed culverts to carry storm runoff under the tracks, protected sections of the roadbed with riprap, and realigned the Cajon Creek channel. The flooding caused so much damage that, in 1939, an approximately 2-mile section of the double-tracked line below Cajon Station was relocated to the west side of Cajon Creek, necessitating the construction of a three-span, steel-plate girder bridge at MP 63.1 (Duke 1995:76; Walker 1978:122).

By 1945, only Ono, Devore, Cajon, and Summit remained as stations on the line between San Bernardino and Victorville. Water stops at Keenbrook and Cajon Stations were discontinued in the early 1950s after AT&SF phased out the steam locomotives in favor of diesel-powered engines (Walker 1978:15, 48-49). The Southern Pacific Company (now Union Pacific) completed a 78-mile bypass route from Palmdale to Colton in June 1967. Known as the Palmdale Cutoff, the tracks roughly parallel the AT&SF (now BNSF) alignment through Cajon Pass on a ruling grade of 2.2 percent (Duke 1995:79).

In 1972, AT &SF realigned the 10° curve at the south end of Summit Station to eliminate derailments and turnovers, which had become all too frequent with long trains. At the same time as the realignment, AT &SF installed a centralized traffic control system over the entire section between San Bernardino and Barstow. The reverse-signal system allowed trains to travel in either direction on the two tracks. The new traffic control system and radio communication eliminated the need for stations, train order offices, and passing sidings, all of which were subsequently removed. Following the line change at Summit, AT &SF initiated a series of minor line changes to reduce maximum curvature from 10° to 6°. In 1977, the realignment project in the vicinity of Sullivan's Curve required the construction of a new bridge over Cajon Creek (Duke 1995:79-80; Walker 1978:253).

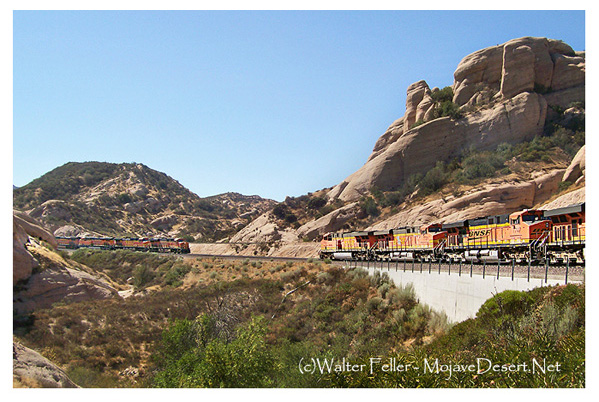

In July 1994, AT&SF and the Burlington Northern Railroad filed papers with the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) indicating their intent to merge. The ICC approved the merger, and on September 22, 1995, the two became BNSF (Kaufman 2005:300, 309).

From: Railroading in Cajon Pass

Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad

Cajon Subdivision

HAER No. CA-2259

SBCo - Railroad History

Railroads

Railroad Building

*

Devore

Keenbrook

Cajon

Summit

Hesperia

Feasibility of the Cajon Pass Railroad