The Formation of the Mitchell Caverns

by Robert M. Norris

The Providence Mountains caves, like most limestone caves in other parts of the world, seem to have had a two-stage

history. Most geologists who have studied the area believe that the two main caves -- Tecopa and El Pakiva -- at

Mitchell Caverns, plus Winding Stair to the north and other small caves to the south, were formed after the Miocene lava

flows on Wild Horse Mesa were deposited. It appears that these flows originally lapped up on the flanks of the Providence

range, somewhat above the level of the caves. At that time the surface of the ground in the vicinity of the park

was much higher than it is today, and the groundwater level stood for a time above the highest part of the caves.

When all the fractures and cracks in the limestone are filled with water, parts of the rock dissolve and and small openings

are gradually enlarged, occasionally to room size. If the groundwater circulates, solution of the limestone can be quite rapid.

Not all limestones form caves; there must be well developed layering or numerous fractures so the groundwater can move

freely, and the rock must be a soluble form of limestone. The lower part of the Bird Spring limestone in the

Providence Mountains

meets the requirements and is a good cave-former.

As long as the groundwater (water table) is above the level of the caves, the rooms are likely to grow larger by

solution, but only when the groundwater drops below the cave floor will stalactites and stalagmites develop.We cannot

be certain what caused the lowering of the water table at at Mitchell Caverns, but two things could have been important. The

first was the erosion of the lavas that lapped onto the flanks of the Providence Mountains. As these were stripped off the

eastern flank of the range, the groundwater level dropped to match the new, lower, ground surface, draining the caves. Perhaps

at the same time, the climate became drier -- we know from plant and animal remains found in the rocks of other parts of

the Mojave that the whole desert region was warmer and wetter during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs than it is today.

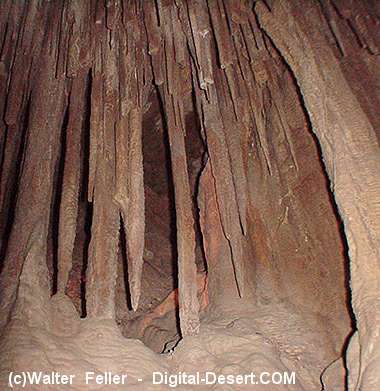

Once the caves were no longer water-filled, the smaller amounts of water seeping into the caves from above would continue to

dissolve limestone. When such water reaches the roof of a cave, it evaporates a little, changes temperature, loses carbon

dioxide, and leaves a tiny lime crust on the ceiling before dropping to the flooor. More evaporation takes place when water

hits the cave floor, and more lime is left at that spot. Stalactites may grow downward quite rapidly -- some straw-like

stalactites have been observed to grow as much as a foot a year. Larger stalactites and stalagmites of course, grow

much more slowly.

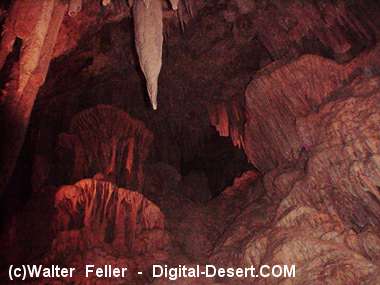

The curtains, pillars, stalactites and stalagmites, and other features now seen in Mitchell Caverns are nearly inactive

under present climatic conditions. Only when heavy rains occur does water enter the caves; most of the time the cave floor is

dry and dusty. This tells us that dripstone, as the cave decorations are called, was formed mainly during wetter climates

than now prevail in the area. Probably the last period of active growth was during the closing part of the Pleistocene

epoch, from perhaps a hundred thousand to about eleven thousand years ago.

The dripstone features are only one of Nature's ways of filling the caves. Shortly after the caves were drained, masses

of rock fell from the ceiling, forming piles of of rubble on the floors of the various rooms. We know that this occured

before dripstone became important, because stalagmites are in some cases built on top of the piles. Even after dripstone

began to form, occasional rock masses fell from the roof; some had stalactites attached. In a few cases broken columns

have been recemented by new dripstone. Some of these recent falls may be related to earthquakes.

Though dripstone formation has slowed and roof collapse is now infrequent, natural processes are still slowly

filling the cave. Dust is blown inside; according to Mr. Mitchell, who at first developed the caves, there was as much as

thirty feet of dust on the floor of Tecopa Cave. Another natural process that can be expected to destroy the caves eventually

is erosion of the mountain that exposes the caves one by one. Some small caves that have been so exposed can be seen along

the trail from the visitor center to the cave entrance.

The history of Providence Mountains and its caves show that nature is never static, but is always destroying some rocks

and forming new ones. As the mountains erode away, the valleys fill with the resulting rock waste, and caves are formed

only to be refilled.

Jack Mitchell

Developer of the Mitchell Caverns ...

-

Mojave Geomorphic Province

Mojave Desert Ecosection